Writing Her Own Story: A Tale of One Woman’s Resiliency

On the edge of Kikinda the traffic and afternoon bustle fade. A child’s broken bike spoke clicks as he rides past a strip of technicolor homes. Across the street, 51-year-old Olgica Aradjanski stands between two gate doors, blonde hair tucked behind her ears. She smiles as she walks through a concrete alley to her candle-making studio, one of the few left in Serbia. The one-window room, comparable to a garage attachment, sits between her home and garden. The exterior is paint-chipped peach, exposing the brick beneath it. Inside, two wax-plattered tables are crowded with silicone molds. Olgica places an aged pot over a hot plate. Her precision reveals her routine, inviting guests into her home and into her world.

Aradjanski preparing to pour wax into a melting pot. (Patterson, 2018)

As she washes wax with cold water from her worn hands in the kitchen, Aradjanski mentions she’d like to write a book about her life someday.

“I’m not sure what the genre of the book would be, but it would be inspirational. There is no way that it would be tragic.”

Aradjanski has been inspired by stories since she was a young girl. They taught her about the inconsistencies of life and how quickly one’s story can rewrite itself.

“Through books I realized I didn’t have to only follow one story, because I had ideas when I was younger of what I wanted, but I was always able to try another story.”

Throughout time one thing that connects people beyond language and culture is storytelling. Whether it’s campfire folklore or a brief conversation over coffee, stories are the chain links of humanity. Despite the place of origin, each person can resonate with another’s narrative. We all understand grief, fear, joy and love. This is simply because we are all human.

Aradjanski’s story as she tells it is one of resiliency, sacrifice and love. She speaks about her life mostly in her native tongue; therefore, various quotes have been translated by Jovan Ciric. This is merely a few chapters plucked from her life.

Chapter One: The Early Years

Olgica Aradjanski was born into a Kikinda blue collar family in 1967. Her mother stayed home while her father worked as a locksmith at a livnica (foundry). Aradjanski was raised primarily as an only child, as her brother was 13 years older.

Aradjanski and Vojvodic throw a birthday party for their dog. (Photo Courtesy of Vojvodic, Date Unknown)

At six-years-old Aradjanski met her best friend, Duda Vojvodic. They attended the same elementary school and were on the gymnastics team together. The two found all types of ways to get into trouble and adventure, Vojvodic said. Her fondest memory of Aradjanski is when they threw a birthday party for her dog in the mid 70s.

“We know each other all of our lives,” Vojvodic said. “She is very tough, big fighter with really big problems who never gives up.”

Aradjanski’s childhood was typical for a Northern Serbian household. At school she daydreamed about becoming an english translator and traveling to the United States, but life had other plans. When she was 13, her father collapsed and died at work. The tragedy caused her story to begin rewriting itself. Her father’s close friend and coworker set up an accounting job at the livincia (foundry) for Aradjanski when she graduated high school.

“On top of that, I started a family immediately after finishing high school,” she said. “While it was something beautiful that happened, unfortunately my dreams weren’t the priority now, but I promised to myself that I wouldn’t forget what I wanted to do and that I would go back to that.”

By the age of 19, Aradjanski was married. Her son was born in 1985, and a baby girl named Marijana with the same soft, chestnut eyes as her mother, was born four years later. Tension in Yugoslavia grew during this period, and the Yugoslav wars began in 1991. The six republics, which included Serbs, Croats, Bosnians, Albanians, Slovenes and others were under a communist regime. The tension between the republics was suppressed by President Tito until his death in 1980. Cultural identities clashed and ethnic cleansing began as war broke out across Yugoslavia.

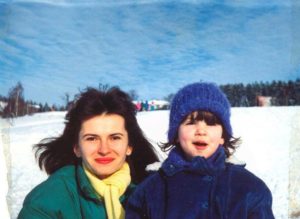

Aradjanski and young Marijana on a skiing trip with their family. (Photo Courtesy of Marijana, Date Unknown)

During the civil war, inflation grew and workers were laid off from their factory jobs. Aradjanski saw this as an opportunity to quit working at the livincia and pursue something that aligned with her interests. Her husband’s grandparents were candlemakers, and they taught him the trade. Aradjanski asked him to pass the skill onto her and suggested they start a candle making business from home. In 1995, after three years of practice and rummaging through his grandparents’ old tools, Aradjanski quit her job.

“I had a feeling that this was going to be very important for me,” she said.

Chapter Two: Life Happens, Again

The couple was getting a hold on the candle business while their children entered adolescence. As unrest grew in Yugoslavia, Serbia was bombed in 1999. Her husband was mobilized to war soon after.

With her husband at war, Aradjanski became a single working mother. Her daughter Marijana still remembers the family tension. “That was three months without knowing what’s going to happen so it was a very stressful, for my mom especially. This is a very important point because this is where everything crashes.” Marijana said.

After her husband returned, family tensions grew, and the couple separated in 2004. Aradjanski moved back into her childhood home with her mother. She gained custody of her son, and Marijana moved into her father’s.

Soon after the split, Aradjanski’s son began lashing out and showing warning signs of mental illness. Aradjanski is protective of her son and his identity, so she didn’t want him or his illness named for the article.

“It is so difficult to talk about,” Aradjanski said. “The experience has been very challenging and very painful for me, but immediately I started to think about how I can turn something bad like this into something that can be useful. In the beginning, I started thinking about how I can use my business for therapy.”

She struggled to support herself with candle-making, but she utilized her creativity to cut corners and budget. Aradjanski made dye from reed trees and decorative string with the rafija plant growing in her garden. Without money for new tools, she hand-sculpted cartoon characters, pumpkins, birthday candles, etc.

Aradjanski’s candle, decoration made with rafia plant. (Patterson, 2018)

“The most important thing that my mom taught me is it doesn’t matter what the situation is, you have to come back to yourself and keep on going, no matter what happens,” Marijana said. “There is always a human connection that gives you hope.”

Chapter Three: A New Vision

Aradjanski’s son began working with her as an aide for his mental health. Together they filled plastic yogurt cups with wax and poured them into molds, their movements synced for hours at a time in front of a long, wooden, dye-splattered table.

As years passed, she noticed an unwillingness to discuss the issue in Serbia. This made Aradjanski realize she wanted to help others who struggle with mental health.

Aradjanski stands in her front doorway. (Patterson, 2018)

“People always had these irrational fears [about mental illness], this started generations ago,” she said. Aradjanski began connecting with therapists and health professionals who were taking a new approach at normalizing conversations about mental illness.

Over the years Aradjanski was involved with Artesa, a women’s entrepreneurial organization in Kikinda, and General Association of Entrepreneurs Kikinda which enabled her to develop close relationships with those in local government. One afternoon in a conversation between the municipal and Aradjanski, members suggested starting a mental health organization in Kikinda. The organization was established in 2015 as Nova Vizija (New Vision). Aradjanski took on the role as president.

“The goal of New Vision is not just starting conversation, it’s also about including all of these people into society and fighting for their rights to have regular jobs,” Aradjanski said.

After the organization began, she continued working on how candlemaking could aid others struggling with mental health. Last year, she employed six people for three months.

In June New Vision sponsored a conference the first of its kind between Serbian mental health organizations and surrounding countries. The groups discussed what laws could be proposed to help those struggling with mental health.

“People always put physical health as more important than mental health, but mental health is equally as important. It is a big factor of how good your physical health actually is,” Aradjanski said.

Chapter Four: Anything But An Ending

Aradjanski leans against the front of her house and laughs. (Patterson, 2018)

Aradjanski still lives in her childhood home. Marijana is studying for a PhD in molecular biology and her son lives at a mental health residential facility a town over. Things are quieter now, other than her black lab that barks in the gated backyard.

As life slows, Aradjanski finds more time to focus on herself—maybe just enough to write that book she’s been talking about.

“I am at the stage where I am in complete balance with myself and everyone around me,” she said.

Storm clouds roll above her home and begin to paint the concrete alley, Aradjanski grows quiet, reflective. She moves the latch on her front gate and smiles. Before waving goodbye, she says if this part of her life was a chapter it would be named “MIRACLE.”

About the Author