Writing Her Own Story: A Tale of One Woman’s Resiliency

Writing Her Own Story: A Tale of One Woman’s Resiliency

On the edge of Kikinda the traffic and afternoon bustle fade. A child’s broken bike spoke clicks as he rides past a strip of technicolor homes. Across the street, 51-year-old Olgica Aradjanski stands between two gate doors, blonde hair tucked behind her ears. She smiles as she walks through a concrete alley to her candle-making studio, one of the few left in Serbia. The one-window room, comparable to a garage attachment, sits between her home and garden. The exterior is paint-chipped peach, exposing the brick beneath it. Inside, two wax-plattered tables are crowded with silicone molds. Olgica places an aged pot over a hot plate. Her precision reveals her routine, inviting guests into her home and into her world.

Aradjanski preparing to pour wax into a melting pot. (Patterson, 2018)

As she washes wax with cold water from her worn hands in the kitchen, Aradjanski mentions she’d like to write a book about her life someday.

“I’m not sure what the genre of the book would be, but it would be inspirational. There is no way that it would be tragic.”

Aradjanski has been inspired by stories since she was a young girl. They taught her about the inconsistencies of life and how quickly one’s story can rewrite itself.

“Through books I realized I didn’t have to only follow one story, because I had ideas when I was younger of what I wanted, but I was always able to try another story.”

Throughout time one thing that connects people beyond language and culture is storytelling. Whether it’s campfire folklore or a brief conversation over coffee, stories are the chain links of humanity. Despite the place of origin, each person can resonate with another’s narrative. We all understand grief, fear, joy and love. This is simply because we are all human.

Aradjanski’s story as she tells it is one of resiliency, sacrifice and love. She speaks about her life mostly in her native tongue; therefore, various quotes have been translated by Jovan Ciric. This is merely a few chapters plucked from her life.

Chapter One: The Early Years

Olgica Aradjanski was born into a Kikinda blue collar family in 1967. Her mother stayed home while her father worked as a locksmith at a livnica (foundry). Aradjanski was raised primarily as an only child, as her brother was 13 years older.

Aradjanski and Vojvodic throw a birthday party for their dog. (Photo Courtesy of Vojvodic, Date Unknown)

At six-years-old Aradjanski met her best friend, Duda Vojvodic. They attended the same elementary school and were on the gymnastics team together. The two found all types of ways to get into trouble and adventure, Vojvodic said. Her fondest memory of Aradjanski is when they threw a birthday party for her dog in the mid 70s.

“We know each other all of our lives,” Vojvodic said. “She is very tough, big fighter with really big problems who never gives up.”

Aradjanski’s childhood was typical for a Northern Serbian household. At school she daydreamed about becoming an english translator and traveling to the United States, but life had other plans. When she was 13, her father collapsed and died at work. The tragedy caused her story to begin rewriting itself. Her father’s close friend and coworker set up an accounting job at the livincia (foundry) for Aradjanski when she graduated high school.

“On top of that, I started a family immediately after finishing high school,” she said. “While it was something beautiful that happened, unfortunately my dreams weren’t the priority now, but I promised to myself that I wouldn’t forget what I wanted to do and that I would go back to that.”

By the age of 19, Aradjanski was married. Her son was born in 1985, and a baby girl named Marijana with the same soft, chestnut eyes as her mother, was born four years later. Tension in Yugoslavia grew during this period, and the Yugoslav wars began in 1991. The six republics, which included Serbs, Croats, Bosnians, Albanians, Slovenes and others were under a communist regime. The tension between the republics was suppressed by President Tito until his death in 1980. Cultural identities clashed and ethnic cleansing began as war broke out across Yugoslavia.

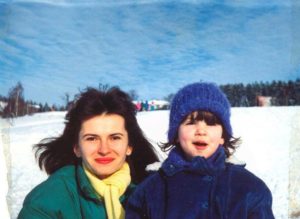

Aradjanski and young Marijana on a skiing trip with their family. (Photo Courtesy of Marijana, Date Unknown)

During the civil war, inflation grew and workers were laid off from their factory jobs. Aradjanski saw this as an opportunity to quit working at the livincia and pursue something that aligned with her interests. Her husband’s grandparents were candlemakers, and they taught him the trade. Aradjanski asked him to pass the skill onto her and suggested they start a candle making business from home. In 1995, after three years of practice and rummaging through his grandparents’ old tools, Aradjanski quit her job.

“I had a feeling that this was going to be very important for me,” she said.

Chapter Two: Life Happens, Again

The couple was getting a hold on the candle business while their children entered adolescence. As unrest grew in Yugoslavia, Serbia was bombed in 1999. Her husband was mobilized to war soon after.

With her husband at war, Aradjanski became a single working mother. Her daughter Marijana still remembers the family tension. “That was three months without knowing what’s going to happen so it was a very stressful, for my mom especially. This is a very important point because this is where everything crashes.” Marijana said.

After her husband returned, family tensions grew, and the couple separated in 2004. Aradjanski moved back into her childhood home with her mother. She gained custody of her son, and Marijana moved into her father’s.

Soon after the split, Aradjanski’s son began lashing out and showing warning signs of mental illness. Aradjanski is protective of her son and his identity, so she didn’t want him or his illness named for the article.

“It is so difficult to talk about,” Aradjanski said. “The experience has been very challenging and very painful for me, but immediately I started to think about how I can turn something bad like this into something that can be useful. In the beginning, I started thinking about how I can use my business for therapy.”

She struggled to support herself with candle-making, but she utilized her creativity to cut corners and budget. Aradjanski made dye from reed trees and decorative string with the rafija plant growing in her garden. Without money for new tools, she hand-sculpted cartoon characters, pumpkins, birthday candles, etc.

Aradjanski’s candle, decoration made with rafia plant. (Patterson, 2018)

“The most important thing that my mom taught me is it doesn’t matter what the situation is, you have to come back to yourself and keep on going, no matter what happens,” Marijana said. “There is always a human connection that gives you hope.”

Chapter Three: A New Vision

Aradjanski’s son began working with her as an aide for his mental health. Together they filled plastic yogurt cups with wax and poured them into molds, their movements synced for hours at a time in front of a long, wooden, dye-splattered table.

As years passed, she noticed an unwillingness to discuss the issue in Serbia. This made Aradjanski realize she wanted to help others who struggle with mental health.

Aradjanski stands in her front doorway. (Patterson, 2018)

“People always had these irrational fears [about mental illness], this started generations ago,” she said. Aradjanski began connecting with therapists and health professionals who were taking a new approach at normalizing conversations about mental illness.

Over the years Aradjanski was involved with Artesa, a women’s entrepreneurial organization in Kikinda, and General Association of Entrepreneurs Kikinda which enabled her to develop close relationships with those in local government. One afternoon in a conversation between the municipal and Aradjanski, members suggested starting a mental health organization in Kikinda. The organization was established in 2015 as Nova Vizija (New Vision). Aradjanski took on the role as president.

“The goal of New Vision is not just starting conversation, it’s also about including all of these people into society and fighting for their rights to have regular jobs,” Aradjanski said.

After the organization began, she continued working on how candlemaking could aid others struggling with mental health. Last year, she employed six people for three months.

In June New Vision sponsored a conference the first of its kind between Serbian mental health organizations and surrounding countries. The groups discussed what laws could be proposed to help those struggling with mental health.

“People always put physical health as more important than mental health, but mental health is equally as important. It is a big factor of how good your physical health actually is,” Aradjanski said.

Chapter Four: Anything But An Ending

Aradjanski leans against the front of her house and laughs. (Patterson, 2018)

Aradjanski still lives in her childhood home. Marijana is studying for a PhD in molecular biology and her son lives at a mental health residential facility a town over. Things are quieter now, other than her black lab that barks in the gated backyard.

As life slows, Aradjanski finds more time to focus on herself—maybe just enough to write that book she’s been talking about.

“I am at the stage where I am in complete balance with myself and everyone around me,” she said.

Storm clouds roll above her home and begin to paint the concrete alley, Aradjanski grows quiet, reflective. She moves the latch on her front gate and smiles. Before waving goodbye, she says if this part of her life was a chapter it would be named “MIRACLE.”

About the Author

Licider hearts: an old tradition as an inspiration for contemporary entrepreneurship

Licider hearts: an old tradition as an inspiration for contemporary entrepreneurship

Licider cookies are colorfully decorated biscuits made of sweet honey dough. They are similar to gingerbread cookies. Traditionally they are made in vibrant red color, and the most popular shape is the heart. Initially, this type of cookies had only square and round shape, but soon bakers and pastrycooks began to use cookie moulds in various forms. In old times they were selling at the fairs, during different festive celebrations and religious holidays, and usually were given as an ornamental present to the dear people. Most often, the boys were giving red-colored licider heart with a mirror to girls as a sign of love and fidelity.

The word licider originates from the German word lebzelter, which means pastrycook who hed a special permission to make cakes with honey. This is an archaic word that is no longer in use. The modern German word for this type of cookies is lebkuchen. The beginning of the history of these cookies is placed somewhere in the 16th century when a similar cookies have made in the monasteries of Central Europe, especially in Germany. During the next two centuries, there was a great expansion of making licider cookies at the territory of Austro-Hungarian Empire. From there it spread to other European countries.

In Serbia, the craft of making licider cookies was brought in 18th by Germans who inhabited the territory of today’s Vojvodina Province. Gradually the Serbs who were candlemakers began to master the skill of making licider cookies. The merging of these two professions stems from the fact that both use bee products. There also were some practical reasons for this. During the winter period when a large number of religious holiday took part, the craftsmen were making candles, and in the summertime when various fairs and festival are held, honey cakes were made.

In Kikinda and nearby there are sveral licider workshops. The most known one is owned by Has family. They have nearly two hundred years of long family tradition of making licider cookies, candies and lollipops. Their products are handmade according to traditional recipes.

Dinka Has, who runs this workshop, says she learned the secrets of this craft from her mother, but she also remembers that as a little girl had watched her grandmother as she works. Now her daughter takes over the family business as Dinka, who is 62 years old, is ready to retire. But as this is a family business, they all work together and Dinka will continue to help her daughters in business. They do not own the store, and they sell products at the fairs, different festive celebrations and manifestations all over the country.

As the biggest challenge in the business Dinka mentioned finding a way to keep the balance between preserving the traditional way of production and adapting to the modern market. “We make the traditional candies such as hard, silk and jelly, but we are constantly increasing our assortment with new flavors such as sour and mint. We also make new shapes. For example, my mother and grandmother made only luše (pipe candy), but we make lollipops in different shapes, such as the figures of popular cartoon characters. We also adopt the ornaments on the licider harts to modern needs. In the past, the inscriptions were not written on harts, while today we write the words such as I love you. Or, if we received an order for some wedding, we usually write a couple’s initials, and like that“.

When it comes to customers, Dinka says they have loyal buyers. “Now the children of my customers come to buy from my daughter. And it often happens that my elderly customers tell that they remember me as a little girl when they shopped from my mom”. When it comes to the age of customers, Dinka says that in her sweets equally enjoy both children and the elderly. It is the same with licider hearts, young people in love, as well as older couples, like to buy them. “Often an older married couple comes to me, and a husband buys a licider heart to his wife to evoke the time when they were young.”

The secret of making and decorating licider hearts has been kept within the family tradition and passing from generation to generation. Preparation of licider cookies takes several weeks. The dough has been traditionally made from honey, flour and water. After mixing, the dough matures for several days. Then the dough is shaped and baked and again left for two weeks to dry. Once dry the liciders are colored by dipping into a specially made color and once again left to dry for a week. The final part is decorating of the ornaments with the frosting which is making of starch, water, and color.

As well as in Serbia, licider cookies are still making in many European countries. In Croatia they are called licitar, in the Czech Republic pernik, in Slovakia medovníky and in Slovenia lect. Each country has own special way of making these cookies. The process of making these cookies from Northern Croatia is added to the UNESCO “Representative List of the Intangible Cultural Heritage” in 2010.

Today, licider hearts are recognized as a brand and souvenir shops are increasingly selling them to tourist. Often they are not made in the traditional way but come from mass industrial production. That is why the survival of small family manufactures is important. They preserve the traditional know-how and authenticity of the product, especially if we have in mind that some product is a part of the intangible cultural heritage.

About the Author

Suvaca in Kikinda

Suvaca in Kikinda

The Suvača cultural monument is located in the territory of the municipality of Kikinda, which belongs to the Northern Banat District. Kikinda is situated at a rather favourable geo-strategic position at 7.5km from the border with Romania and 60km from the border with Hungary and is the largest borderline city along the entire Serbian-Romanian border.

The Kikinda Suvača mill is a cultural monument of outstanding importance for the Republic of Serbia. It is the only preserved horse-powered grain mill in Serbia. On a European scale, this type of mill is exceptionally rare. Suvača is an authentic mill, more than one hundred years old. In addition to its architectural, cultural, historical and intangible value, Suvača is also exceptional for its symbolic value. It is one of the symbols of the city of Kikinda, kindling a sense of community. For these reasons, there is a great interest in its rehabilitation, both at national and local level.

photo credit: Foto Sretenovic Kikinda

The Suvača mill is today owned by the Municipality of Kikinda and is managed and taken care of by the National Museum of Kikinda.

Suvača is one of the symbols of Kikinda. The local population considers it an important symbol of their identity. Members of the local community are proud of Suvača, and they regard it significant and valuable, and are glad to show it to their guests. Suvača is amongstthe oldest symbols of Kikinda; and which is even more important, it is the symbol of Kikinda’s farmers, that is, the keeper of the identity of “ordinary” people originating from families of farmers regardless of their national or religious affiliation.

The primary vision of the Suvača cultural monument is its transformation into a community center, which is to assist development and improvement of cultural needs of the local population and development of sustainable entrepreneurship based on resources of non-material cultural heritage. This vision foresees a transformation of Suvača into a point for cultural amenities, education and development of skills of the local population, as well as its conversion into a sales space and place for development of brands of local products based on the identity of Suvača and non-material heritage of this area.

In this manner Kininda-based Suvača is to be represented as a unique building of traditional architecture that preserves and evoques memories of traditional life of Vojvodina farmers, tastes of the nature and rural life and a point for development of sustainable entrepreneurship and economic strengthening of the local population, primarily of women and the youth. This vison will be establised by 2019. whene Suvaca will be rehabilitated. Funding for this acitivity came from EU IPA founds. In cooperation with Romanina partners, National Museum Kikinda will work on promoting Suvaca and dray mills history in this part of Europe as a touristic attraction.

photo credit: Foto Sretenovic Kikinda

About the Author

Nasuvo with sour-cabbage

Nasuvo with sour-cabbage

One of the most typical Banatinan dishes is nasuvo (in Serbian meaning something dry). During fasting people prepared four types of the dish nasuvo as it can be made with poppy seeds, walnuts, potatoes and with sour cabbage. After World War II, fasting almost disappeared in Banat and the traditional types of nasuvo were changed as people started putting animal fat in it. The dough is made the same way but with the addition of 3 eggs. The following recipes are for the fasting types, without fat.

Recipe

- 250 grams flour

- water

- 500 grams of sour-cabbage cut into cubes or strips

- one small onion finely chopped

- 1 tsp of oil

- 1 tsp of salt

- pepper

How to cook

Combine the flour and a small amount water in a bowl and mix with your hands until you have a firm, but not sticky dough. Add more water as needed. Then, place the dough on a floured surface, roll it out to a thickness of 3 mm, and cut it into 5 cm by 5 cm pieces. Next, bring a pot of salted water to boil on the stove. Add the pasta and boil until cooked. After the boiled pasta is fully cooked, rinse it with water.

In a small amount of oil, lightly fry the onion. When the onion turns yellow, add the cabbage. Cook the cabbage until tender. Add a little bit of salt and mix well. Combine the pasta (cooked dough) together with the cabbage, cooking over a low heat on the stove until all the ingredients blend together. Serve warm.

About the Author

Nasuvo with walnuts

Nasuvo with walnuts

One of the most typical Banatinan dishes is nasuvo (in Serbian meaning something dry). During fasting people prepared four types of the dish nasuvo as it can be made with poppy seeds, walnuts, potatoes and with sour cabbage. After World War II, fasting almost disappeared in Banat and the traditional types of nasuvo were changed as people started putting animal fat in it. The dough is made the same way but with the addition of 3 eggs. The following recipes are for the fasting types, without fat.

Recipe

- 250 grams of flour

- water

- 150 grams of minced walnuts

- 1 tsp of sugar

How to cook

Combine the flour and a small amount water in a bowl and mix with your hands until you have a firm, but not sticky dough. Add more water as needed. Then, place the dough on a floured surface, roll it out to a thickness of 3 mm, and cut it into 5 cm by 5 cm pieces. Next, bring a pot of salted water to boil on the stove. Add the pasta and boil until cooked. After the boiled pasta is fully cooked, rinse it with water.

Mix 150 g of minced walnuts and 1 tsp of sugar with the cooked pasta.